The Burden of Proof and Anti-corruption

Thomas J. Samuelian

July 12, 2002

Synopsis

| Disclaimer – The views expressed herein are not endorsed by the Government of Armenia or the World Bank. They are presented as part of academic discourse on the theory of the rule of law and anti-corruption principles. |

Put succinctly, corruption is the abuse of public office for private gain. This paper explores one of the features of a legal system that creates the potential for such abuse. Currently in Armenia and in most countries, the burden of proof is on the private citizen to challenge adverse state decisions. This gives the official an advantage over the private party, securing the official with both the opportunity and economic incentive to deny citizen requests or delay or complicate them in order to extract bribes (favors/influence). The advantage that is being leveraged by the official is an artifact of the legal system, not intrinsic to the “substantive policy” embodied the legal norm. By shifting the burden of proof to the official — where feasible, consistent with the public interest — the official’s opportunity to extract bribes is cut off, since any individual official across a widely dispersed bureaucracy would be hard-pressed to collude with a relatively more easily monitored court to reach a decision that is contrary to law and the citizen’s interest. In addition, the problem of monitoring and oversight would become more manageable if the burden of proof were shifted to the official. Instead of having to clean up, oversee and monitor tens of thousands of officials and hundreds of thousands of transactions, one would only have to monitor and oversee 100-200 judges and probably under ten thousand cases per year.

This method of reducing the opportunity to extract rents does not require radical change in the substantive requirements of the law (which is not to suggest that such substantive reform may not be beneficial). It does not change policy underlying the law. Regardless of who bears the burden of proof the system should theoretically produce the same results. It is possible to further fine tune the incentives to reduce abuse of this shifting of the burden of proof. Officials could be sanctioned for groundlessly pursuing cases against private parties, perhaps, delays in promotions, removal from office or fines, and private parties fined for groundlessly refusing to follow the law, forcing the official to go to court in order to seek enforcement.

Furthermore, shifting the burden of proof has the desirable effect of reinforcing the presumption of innocence, which is an antidote to the prosecutorial tilt of soviet and post-soviet legal attitudes. It also removes the incentive to seek public office for private gain by reducing the opportunity for rewards and greatly increasing the costs and effort to misapply the law to extract rents. Most importantly, it does this by using the incentive system and logic that underlies existing values and behavior patterns to redirect the undesirable behavior, instead of using an overlay of supervisory or coercive measures to do so.

Shifting the burden of proof may be viewed as a balancing measure that levels the public-private playing field and compensates for the lack of professional advisory services and the inability of clients to pay for such services. This policy, therefore, not only de-incentivizes corruption, but also accelerates reduction of the size of the public sector at the same time. However, it is a smart reduction – it does not impose across the board cuts or drive the good from the system. Rather it retains the conscientious who are applying the law properly without taking bribes and encourages the exodus of the corrupt from the system. It gives conscientious public servants the incentive to do their jobs well and corrupt public servants the incentive to resign, since it is no longer lucrative to stay on the job. Corruption cannot be significantly reduced without reducing the size of government and sphere of government regulation to a level that society can afford, assuring efficiency, high quality service and reasonable civil service salaries. The most common objection to this truism is that reductions in force are unpopular and take political will. Shifting the burden of proof achieves reductions in force without fiat.

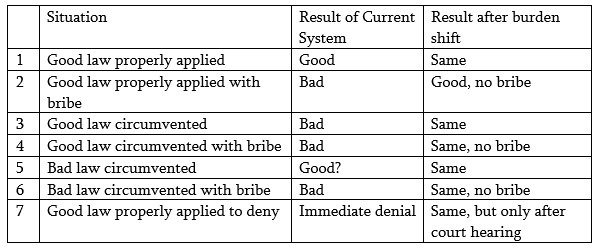

Another possible objection to is that shifting the burden of proof delays the deterrence or preventive feature of the current system. As the chart below shows, this objection is fallacious, and the benefits significantly exceed any losses in deterrence or prevention. Indeed, any negative impact from shifting the burden of proof could, and probably does, take place under the current system, for the price of a bribe (or other illicit influence). Moreover, shifting the burden of proof can be a temporary measure, applied until the system streamlines and cleanses itself. During the interim any abuse due to delay in punishment would be significantly outweighed by the reduction in bribe-taking and streamlining of the system. In any event, in those situations where shifting the burden of proof would do some irreparable harm to society, the burden of proof can and should remain as it is (recognizing, of course, that circumvention of the current system is still possible and usually doubly harmful to society – a violation of the legal norm compounded by extortion or bribery).

Of course, shifting the burden of proof is not sufficient on its own to achieve a corruption free society, but it may be a useful tool. In general, it is necessary to streamline and simplify laws and institutions so that people do not circumvent them. Given the widespread manifestations of low-level corruption and circumvention of the law in Armenia, it may be more effective to consider ways of using the existing attitudes and behaviors to bring about change. In any event, it is usually easier to conform “words on a page” to practices and attitudes than to conform practices and attitudes to “words on a page.” In doing so, it is necessary to apply principle of “legal efficiency”:

Laws and regulations should be no more complex than

|

Ultimately, the goal should be voluntary compliance with laws and regulations that Armenian society supports as a means to secure a globally competitive, corruption-free environment that makes Armenia the most desirable place for Armenians to live, work and create.

Law enforcement cannot be overlooked and has its place. However, it is not cost- effective or feasible, and probably would not be desirable, to apply the level of oversight and punishment necessary for these to be the primary measures to eradicate corruption. Indeed, these methods can be destructive and are prone to corruption and abuse. Moreover, there is reluctance toward applying such methods in small, tight-knit societies, witness the low level of bribery prosecutions in Armenia (less than 50 prosecutions last year, with only a handful of prison sentences). While it may at first glance seem radical or even risky to shift the burden of proof from the citizens to the state, compared with the main alternatives –namely oversight, substantive legal reform, and punishment — the risks are probably lower with fewer negative side effects. Thus, shifting the burden of proof deserves serious consideration as an anti-corruption measure that is likely to have a net positive effect with few expected or unexpected negative side effects.