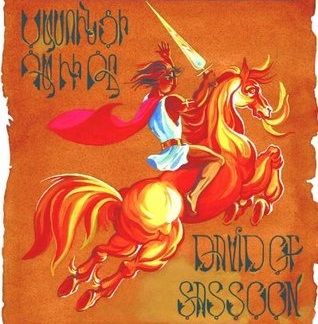

David of Sassoon

by Hovhannes Toumanian

Translation by Thomas Samuelian

INTRODUCTION

The name “David” comes from the Hebrew for “the beloved one.” Like the Old Testament David who slew Goliath, David of Sassoon is the beloved, national hero, the defiant and self-reliant youth, who by the grace of God defends his homeland in an unequal duel against a titanic oppressor.

The David of Sassoon presented here is Hovhannes Toumanian’s captivating rhymed version of the third cycle of the epic. The epic spans four generations of the house of Sassoon, a mountainous enclave of the Armenian highlands, west of Lake Van and Mt. Ararat, known for its hearty folk and indomitable spirit. The epic took shape in the 10th century based on an oral tradition spanning centuries. The earliest written reports of the epic were made by Portuguese travelers in the 16th century. The basic text of the epic was first recorded in 1873 by Fr. G. Srvandzdyants. The full epic is a hefty tome that, one can imagine, took medieval tellers days to recite, easing the boredom of the long, lonely winters for these highland shepherds.

The epic begins with two brothers, Sanasar and Balthasar. Some scholars link them to the brothers Adramelek and Sarasar, the sons of Hezekiah (2 Kings 19:37, Is. 37:38), the king of Israel during the seige of Jerusalem by Sennecherib, King of Assyria. Movses Khorenatsi, the father of Armenian history (II.5,7, III.55), considered the Artsruni dynasty of Armenia, which ruled in and around Vaspurakan (Lake Van to Lake Urmia) and reached its height from 908 to 1021, to be descended from Sanasar. According to Armenian tradition, the two sons settled near the mountain called Sim, which some have identified as a mountain in Sassoon. The pair of brothers resurface in the Armenian epic as the immaculately conceived sons of the Armenian princess Dzovinar, who was taken from Armenia to Baghdad by the Caliph when most of Armenia was under Arab domination from (7-9th centuries). The Caliph decides to kill them, but before he can, they escape to Armenia. After slaying dragons, building cities, and restoring Armenia to prosperity, the brothers return to Baghdad to rescue their mother.

In the epic of David of Sassoon, the Moslems (referred to as Musr or Egypt in this version of the epic) and their leader (referred to Melik – king) may have displaced the Assyrians, and two thousand years of history may be compressed into a single storyline, but the north-south geopolitical dynamic between Armenia and Mesopotamia persisted in the people’s collective memory and remained deep rooted in the repertoire of Armenian oral tradition.

The next cycle is the story of David’s father, Lion Mher, who is the epitome of the noble, wise, fair and self-sacrificing father-king. Approaching old age without an heir, he accepts with gentility the passing of his generation as the price of the next generation. As the reading from the Armenian requiem states, “except a grain of wheat falls into the earth and dies, it remains alone; but if it dies, it bears fruit.” (John 12:24). Lion Mher represents the strength of nature and rectitude of character that bears fruit in his son, David, who is raised an “orphan, no keeper on earth.”

David’s story resonates not only with the Old Testament David, but also with the battle between Hayk of Armenia and Bel of Assyria. Hayk is the Armenian Orion (Job 9:9), the deified archer- protector-forefather of the Armenians. His deification has been linked by some scholars to the Prometheus story in Greek mythology. In Movses Khorenatsi’s history, the story of Hayk’s titanic battle with Bel is one of the key episodes in the formation of the Armenian people. Hayk was a handsome, friendly man, with curly hair, sparkling eyes, and strong arms. He was a man of giant stature, a mighty archer and fearless warrior. Hayk and his people, since the time of their forefathers Noah and Japheth lived in and around Mt. Ararat (whence the name of the region below Ararat, Nakhichevan – “the place where Noah descended”). To the south ruled a wicked giant, Bel. Bel tried to impose his tyranny upon Hayk’s people. But proud Hayk refused to submit to Bel. After major battles, Hayk delivers his people and restores freedom to his homeland. This north-south struggle is a recurrent theme in Armenian history, repeated in the century from 750 to 850 between the Armenian Bagratuni kingdom of Ani and their Arab overlords. According to some scholars, a century later, David Bagratuni surfaces as David of Sassoon, the fearless, freedom-loving youth, and Hovnan Bagratuni as Uncle Ohan, the cringing appeaser.

An epic cannot be summed up in a single word or from a single point of view. Each reader and listener will relate to certain characters and events in different ways. Nevertheless, the image of David of Sassoon, his nobility, fearlessness, strength, and simplicity, while having special significance for Armenians, has a universal appeal that speaks to all peoples.

Finally, a word about this translation. There are several English translations of David of Sassoon, including a blank verse translation of Toumanian’s version of this work. So why this translation? Primarily because no other English translation has attempted to replicate the rhymes and rhythms of the Toumanian version, in short, the music of the poetry that draws the reader in and pulls the reader forward through line after line of this marvelous epic work.

Thomas J. Samuelian Yerevan, August 1999

I

Great Lion Mher, with his noble pride,

for forty long years ruled Sassoon far and wide.

His rule was so awesome that in his day,

across Sassoon’s peaks even birds feared to stray.

Far from the highlands where Sassoon was found,

his dreaded fame spread with a thunderous sound.

And praise for the high deeds of Lion Mher,

on thousands of lips, in one voice, filled the air.

II

He ruled in Sassoon with lionly might,

the prince of the highlands, unchallenged in right.

For forty long years he ruled without foe,

and in forty long years he knew not one woe.

But now as old age upon him descended,

this valiant man’s heart a pang apprehended,

which prompted the aging grand hero to ponder:

“My life’s autumn days will soon take me yonder,

the captive of earth and its black sandy cloak.

The fame of Mher shall vanish like smoke,

and my name, and my might, and my glory shall pass,

in my orphaned and leaderless realm shall amass

thousands of bandits and fiends on the make,

no heir have I left, no successor to take

my sword in his hand for Sassoon’s protection,”

so thought the great prince in pensive dejection.

III

Then one day, as he thought, his grey eyebrows knit tight,

an angel from heaven, in fiery light,

came to the prince, feet fixed on a cloud,

bringing a message, proclaiming aloud:

“Greetings! your highness, O Sassoon’s great lord,

your voice to God’s throne in high heaven has soared,

and soon shall he grant you the heir that you seek.

Heed me well, though, prince Mher, great king of this peak,

on the day that the Lord gives effect to your prayer,

neither you nor your wife shall he suffer to spare.”

“May God’s will be done,” said Mher without sigh,

“Death is our lot; all mortals must die.

But when in this world we’ve a child in our stead,

through our child we live, although we be dead.”

And then in a flash, the Angel took flight,

and nine months and nine hours from that joyous sight,

to Lion Mher a child was born,

and he called his cub David. On that happy morn,

he summoned his brother Ohan of Great Voice,

and his realm he bequeathed, no time to rejoice,

to his brother Ohan and his newly born son,

knowing his days and his wife’s were now done.

IV

In those times, reigned a king, over Egypt victorious,

called Melik of Musr, mighty and glorious.

As soon as he learned of Great Mher’s demise,

he set for Sassoon to conquer a prize.

Ohan of Great Voice trembled in fear,

bowing his head, as the warlord came near.

Down on his knees, begging he said,

“You be our master,” quaked he with dread,

“So long as we’re under the force of your sway.

We’ll be your true servants, your tribute we’ll pay.

But on one condition, our land must remain,

untouched and intact for as long as you reign.”

“No,” said Melik, “your whole nation must go,

under my sword their submission to show,

and prove that whatever my policy be,

no native of Sassoon shall rise against me.”

Ohan called his people from near and from far.

They passed one by one ‘neath Melik’s scimitar.

All except David, who try though they did,

refused to do honor as Melik had bid.

The crowd dragged him forward by force to his foe.

Raging, he tossed them away, high and low.

He grazed his small finger against a large rock,

emitting a lightning bolt to the crowd’s shock.

“This rogue, he is trouble, I must kill him off,”

said the King to the elders, who started to scoff.

“King,” they protested, “you’re mighty and strong.

How could this young lad do you any wrong,

though he were fire from head down to foot,

after everyone under your sword you have put?”

“You think you know best,” said Melik, with alarm.

“But be warned, if upon me should ever come harm,

upon this boy’s head shall the penalty rest,

as this day’s defiant events do attest.”

V

At the time of this clash, David the great,

was but a small boy, of seven or eight.

A boy though I say, he was strong as could be.

All were the same to him, man, beast or flea.

It’s an old saying, but truth it does hold,

“Eat up your porridge, grow up strong and bold.”

But pity this child, no keeper on earth,

although Mher’s son, they knew not his worth.

Ohan of Great Voice had a mean, wicked wife.

Her tongue she first held, then started the strife:

“I’m only one person, with thousands of cares,

enough mouths to feed, without rearing theirs.

What did I do that you took in this knave?

I’m telling you straight, I’m nobody’s slave.

I’ll bury this boy, if you don’t send him packing,

so set something up, work’s what he’s lacking.”

And then she began to moan and complain,

that she was so poor, that all was in vain.

Her burdens were boundless, at least in her eyes:

“I’ve no keeper, no helper, no pity, no prize.”

Ohan went and thought, now what shall I do?

He found iron boots, for the boy as a shoe,

and a large iron rod, to sling on his back.

A shepherd he made him, Sassoon’s sheep to track.

VI

Our hero the shepherd tended his sheep.

He wandered the hills of Sassoon high and steep.

Hey, my dear highlands,

O Sassoon’s highlands,

He shouted in joy, his voice echoed so,

rumbling it bounced from the peaks high and low.

And the birds and the beasts fled their lairs and their nests,

scampering on rocks, with no where for rest.

David gave chase o’er the hills and the vales,

the fox and the deer, the hares and the quails.

Gathering them up, he climbed top the rocks,

he mixed them all up with the sheep in his flocks.

Down to the town of Sassoon they stampeded,

with noise, dust and uproar, they brayed and they bleated.

The city folk cried, their eyes not believing.

The livestock charged forth, the town’s life upheaving.

Oh help, someone save us!

The children cried out.

The grown-ups in panic

their work threw about.

Wherever they hid, at home, church or store,

they locked up the windows and bolted the door.

When David arrived and stood in the square,

he looked all about, but no one was there.

“Yo there, he shouted, it’s too soon to sleep,

I’ve come with your goats, and brought you your sheep.

Goatherds and shepherds, get up from the sack,

for each one I took, ten I’ve brought back.

Hurry, come get them and take them away

to your barns for safekeeping, or else they will stray.”

But no one came out, the doors didn’t budge.

Back to the hills, too tired to trudge,

he pulled up a rock and rested his head,

and soon fell asleep, the square for a bed.

When the sun rose, the town’s folk emerged

at old Ohan’s house, they quickly converged.

“Hey there, old Ohan of the Great Voice,

it’s you or the kid, you’ve left us no choice.

How could you put our whole flock in his hands?

The town’s filled with beasts, he’s ruined our lands.

He can’t tell a fox from a lamb. What a mess!

So find him another job, quick, and God Bless!”

VII

Ohan rushed away his nephew to see,

“Uncle, tread softly, these goats like to flee,”

said David, who’d spent all night keeping them there.

But as he approached, the ears of a hare

perked up and he dashed away into the wood,

and David gave chase as fast as he could.

Over the hills and over the dales,

he chased the grey hare through the mountainous trails.

He caught him and brought him right back to the camp,

mixed him in with the goats, and then smiled like a champ.

“The black ones, God bless them, I like them just fine,

but, Uncle, the grey ones, they won’t stay in line.

All day, yesterday, they hopped all around.

In order to catch them, I covered some ground,”

Ohan took a look at David’s new boots.

Iron shoes were not equal to David’s pursuits.

The rod like the boots was worn away,

so much had he run in only one day.

“David, my lad,” he said with affection,

“Those grey ones abused your valiant protection,

I’ll leave you no more to their wily devices,

tomorrow, for you cow pasture suffices.”

Ohan went his way, and on the next morn,

he brought new steel boots for the ones that were worn,

and a new iron staff for David’s strong hand,

and made David guard of Sassoon’s pasture land.

VIII

Up to the pasture he went with his herds,

to Sassoon’s still highlands, fair beyond words.

O my dear highlands,

Sassoon’s sweet peaks,

my heart in your bosom

finds just what it seeks.

He shouted aloud in his voice pure and strong.

The canyons and mountain tops rang with his song.

The birds and the beasts fled their nests and their lairs.

They scampered away to avoid David’s snares.

As David pursued them through hill and through dale,

he chased them around every mountainous trail.

The wolf and the leopard, tiger, lion and bear,

he caught and mixed in with the herd in his care.

And drove them back down to the town of Sassoon,

with rumbling and grunting in mid-afternoon.

The town’s folk again were aroused from their chores

by the charging of beasts, they were drawn out of doors:

“Oh, no, get away,”

the young and old cried.

Their hearts in a panic

their work flung aside.

And they fled to their houses, their churches and stores.

They locked up the windows and bolted the doors.

When David arrived and stood in the square,

he looked all about, but no one was there,

“How early you city folk turn in for sleep!

Come, see what’s become of the herd in my keep!

For each cow and ox I’ve brought ten in its stead,

and for each ten you gave me, twenty I’ve bred.

Hurry up, come on out, and take them away,

or else your new cattle will run and go stray.”

But no one came out, the doors didn’t budge,

back to the hills, too tired to trudge,

he pulled up a rock and rested his head,

and soon fell asleep, the square for a bed.

When the sun rose, the town’s folk emerged.

At old Ohan’s house, they quickly converged.

“Ohan, we’ve had it, now look what he’s done.

Our cattle and oxen, he’s let loose to run.

He can’t tell a lion from an ox or a cow.

Whatever it takes, get rid of him now.

This boy, hear us well, spells nothing but trouble

He’ll make our fair town a bear’s den and rubble.”

IX

Try as he might, he didn’t fit in.

The boy was a rebel, Ohan couldn’t win.

For David he fixed up a bow and some arrows,

“You’re off to the hills to hunt quail and sparrows.”

David took up the bow and was ready to roam.

Leaving Sassoon, his folks and his home,

he marched through the barley fields, up the steep trail,

and started to hunt the sparrows and quail.

At dusk he caught sight of a very poor shack,

he sprawled on the floor, the hearth to his back.

In the shack an old woman, who’d known of his dad,

lived alone, without children, and took in the lad.

One day he returned from his regular hunt.

The old woman yelled to him, plainly and blunt,

“I’ll be damned, you’re his boy, the King’s only heir.

You’re David, the son of Lion Mher.

I am old and my arms and my legs they are shot.

My worldly possessions are myself and this plot.

So why must you trample it on your sorties

and wreck my year’s crops, do tell, if you please?

And what kind of hunter seeks game in these parts?

Seghanasar is the place to practice those arts.

Dzdzmaga was the gate to the King’s hunting ground.

There the deer, and the goats, and the wild sheep abound.

Go there, if you’re looking to hunt real game,

Instead of round here where the creatures are tame.”

“Why do you scold me, in words sharp and base,

I am young, I’d no knowledge of this special place.

Where, please do tell, is the King’s hunting ground?”

“Well, go ask your Uncle, he knows where it’s found.”

X

The next day at dawn he was at Ohan’s door.

With his bow in his hand he gave Ohan what for.

“You never said that my dad had a grove,

in the mountains where game used to roam by the drove,

where the rams ran about with the wild goat and deer.

Get up, Uncle Ohan, let’s go, is it near?”

“Oh David,” cried Ohan, “who told you these things?

May they be struck dumb, oh, how this stings!

That mountain, my lad, is not in our hands.

The game that roamed there have been snatched from our lands.

It’s not like it was in your dad’s blessed day.

And what days those were! Where have they gone?

How many times did we eat venison!

When your father died, God forsook us.

The Melik of Musr then overtook us.

With his troops he attacked, but we were outmanned.

He stole all the game and plundered our land.

Where deer and goats roamed, now there are none.

So it was written, so it was done.

Now it’s all past, go back to your work.

If the Melik gets wind of this he’ll go beserk.”

David scoffed, “The mean Melik can do me no harm.

Why should my inquiries cause him alarm?

Let the Melik of Musr stay in his home.

What business does he have in our parts to roam?

Get up, Uncle Ohan, remember your bow.

To the mountainous hunting ground we’ve got to go.”

So they ventured to Lion Mher’s hunting ground,

but when they got there, they heard not a sound.

The trees were cut down, the fences destroyed,

the look-outs laid low, the land was a void.

XI

When it grew dark, they decided to stay.

Ohan of Great Voice had had a long day.

His head on his quiver he rested, then snored.

David however was restless and bored.

His mind was submerged in a deep sea of thought,

when in the dark a shimmering light caught

his eye and he started and jumped to his feet,

and raced toward the light with his legs fast and fleet.

Bounding he ran to the top of the peak,

then he glimpsed a white stone in these parts dark and bleak.

The white marble stone was split in the middle,

and a flame burnt bright there, “What a puzzling riddle!”

Thought David as he ran as fast as he could

to rouse Uncle Ohan to see if he would

wake up and examine this startling sight.

“Uncle Ohan, enough sleep! Come see the light,

settled on top of the mountains afar.

Get up, Uncle Ohan, it’s bright as a star

that bobs up and down on a white marble sheet.”

Ohan crossed himself twice as he rose to his feet.

“Alas, my poor lad, the light that you’ve seen,

is all that is left of the altar serene,

of the Church of Our Lady, our keeper and hope.

The convent and church on Maruta’s slope,

is called Charkhapan, where your dad went and prayed,

each time he set forth and fierce battle made.

When your father died, God forsook us.

The Melik of Musr then overtook us

Maruta convent he razed to the ground,

but the altar light pierces the darkness profound.”

XII

When David discovered the convent’s sad fate,

He called to old Ohan, “Dear Uncle, please wait!

I am an orphan, no keeper on earth.

You are my father, though not by birth.

I want to stay here on Maruta’s peak,

until I’ve rebuilt our convent unique.

Provide me, my keeper, five hundred skilled men,

and five thousand workers to build it again.

Just as it was, we’ve no time to lose.

Send them this week, please don’t refuse.”

Just as he promised, Ohan brought a corps

of five thousand five hundred superior

workers to rebuild the convent on high.

Banging and clanging, it rose to the sky,

just as it was, in all of its glory,

the Church of Our Lady, a blessed promontory.

The monks to the convent quickly returned.

Chanting soared up again, candles were burned.

David came down from the convent sublime

restored to the splendor of Great Mher’s time.

XIII

It didn’t take long before Melik got word,

“David’s the prince now or haven’t you heard?

He’s rebuilt the convent dear to his dad,

and for seven years now, no tribute you’ve had.”

The Melik exploded and summoned his lords,

“Badin, Gozbadin, claim my just rewards,

Syudin, Charkhadin, set forth straight away.

Leave no stone unturned, Sassoon has to pay

a price for its insolence. Strike hard and swift.

Remind my dear subjects that tribute’s no gift.

And bring forty maidens, radiant and bright,

and bring forty short maids of milling height,

and bring forty tall ones my camels to load.

They’ll work as my servants and tend my abode.”

Gozbadin saluted his master and king,

“Your tribute in gold and the maids we will bring.

Your wish, King of Egypt, is our glad command.

We’ll vanquish the rebels in Armenia’s land.”

The Melik, his wife and his daughter made merry.

They danced and they sang, “Armenia we’ll bury.

Gozbadin, the Bold, on Sassoon will make war.

He’ll bring us back servants and gold coins galore.

And forty bright maidens and forty short maids,

and forty tall ones, who’ll work as our aides.

They’ll load up the camels and milk the red cows,

and churn creamy butter and tend the fat sows.

Gozbadin! Gozbadin! our knight, strong and brave,

you’ll whip David handily, he’s just a knave.”

Gozbadin swelled up and nodded with pride,

“Thank you, my ladies, all boasting aside,

if you will with patience my victory await,

we’ll have more to dance for, we’ll all celebrate.”

XIV

With songs and with laughter

his armed men went after,

Sassoon and its people and when they arrived,

Ohan lost his voice and a welcome contrived,

With salt and bread,

with tears and dread,

he bowed down his head

and humbly pled:

“Whatever you want, oh, please, take your pick,

our maids or our hard dug gold in coin or brick,

rosy cheeked maidens, so bright and so fair.

Just don’t wreck our lands or rip us asunder.

It’s God’s realm above and Melik’s down under.”

Ohan called together the rosy cheeked girls.

Gozbadin checked them out as if they were pearls.

And when he’d selected, he ordered them held

in a locked stable, then with pride he yelled:

“Forty young maidens, radiant and bright,

forty short maidens of milling height,

forty tall maidens the camels to load.

They’ll all work as servants in Melik’s abode.

With glistening gold our king they’ll adorn,

while their friends in Armenia wear black and mourn.”

XV

O David! where are you, Armenia’s protector?

Dash open the rocks, our convent’s erector,

and come to the square, Sassoon’s plight is bleak.

And David came down from Maruta’s peak

to the old woman’s plot where a rusty sword laid,

trampling the turnips, he reached for the blade.

“David, you fool, get out of my garden,”

scowled the old woman, “God beg my pardon,

is my plot the only place that’s caught your eye?

A curse on you, David, may you suffer and die.

Just look what you’ve done, you’ve levelled my field.

Nothing is left of my winter crop’s yield.

What will I live on, can you tell me that?

You’re such a foolish and clumsy, spoiled brat.

Were you truly brave, you’d take up your bow,

and rule your dad’s realm as he did long ago,

and claim your birthright and live as you ought,

for too long you’ve given Sassoon not a thought.

The Melik’s sent forces to sack it today.”

“Why do you scold me?” he asked in dismay,

“What does the Melik dare take from me?”

“Everything, David, go home and you’ll see.

The Melik is ready to gouge out your eye,

while you’re sitting here all alone idly by.

O David, wake up, he’s taking it all.

He’s sent in his warriors to spread ’round his gall.

Gozbadin and Badin led the attack,

Charkhadin and Syudin brought up the back.

They’re plund’ring Sassoon and gathering their loot.

Forty gold sacks is their price for tribute,

and forty young maidens, radiant and bright,

forty short maidens of milling height,

forty tall maidens the camels to load.

They’ll all work as servants in Melik’s abode.”

“Why do you curse me, old woman, pray tell?

Where I can find these fiends, I’ll give them hell.”

“Where are these fiends? Curse my old ears!

How could this be his son? Brings me to tears!

You’re munching on turnips out here in the cold,

while Gozbadin is in your house counting your gold,

and filling the stable with your town’s fair maids.”

Tossing the turnip, he reached for his blade.

He went to his house, Gozbadin was there,

weighing the gold with cold, greedy care.

Charkhadin and Syudin were holding the bag.

Ohan of Great Voice his tongue didn’t wag.

He stood there in silence, his head lowly bowed.

Wringing his hands, he was downcast and cowed.

When David saw this, his eyes flushed with rage.

“Gozbadin, get up, get back in your cage,

This gold is my dad’s, it’s mine to mete out.”

Gozbadin called Ohan, “Rein in this lout.

Are we getting our tribute this minute or what?

If we don’t, mark me well, no ‘if and or but’,

I’ll tell the Melik to launch an invasion.

He’ll raze Sassoon town, there’ll be no dissuasion.

To the ground he will burn it and then plant a park.”

But David unfazed did not fear his bark.

“Get out, dogs of Egypt. Flee while you can.

The braves of Sassoon fear no living man.

Did you think we were dead? Or we gave up the ghost?

That you can take tribute and rule us and boast?”

Then David grew angry, and picked up the scales.

He smashed in Gozbadin’s head to shrieks and wails.

The shards of the scales pierced holes in the walls,

and fly to this day like sharp, spiked cannon balls.

The warriors of Musr fled, leaving the gold.

Armenia was safe, praise David the bold.

Gozbadin and Badin quickly turned tail.

Charkhadin and Syudin followed their trail.

XVI

“Dear Uncle, how could you, what can I say?

We’ve great heaps of gold, yet you treat me this way?

You’ve made me a servant, no keeper on earth,

abandoned to others, is that all I’m worth?”

Ohan lost patience and cried out, “You fool!

The gold was our shield against Melik’s fierce rule.

We kept it so that he would turn a kind eye.

You’ll see what will happen when we defy.

He’ll ruin Sassoon and plunder our land.

Who can oppose him, his onslaught withstand?”

“Hold it, dear Uncle, he’ll answer to me,

I’m not afraid of him, just wait and see.”

Then he knocked down the door to the dark,

dreary stable, and rescued the maids, before Ohan was able

to say one more word. David told them with glee,

“Long life wish for David, go home, you are free!”

XVII

Battered and bloodied,

tattered and muddied,

the warriors of Egypt fled toward their home soil.

Glimpsing their coming caused noise and turmoil.

The women of Egypt first shouted in joy.

They clapped from their rooftops, “Ahoy, there, ahoy.”

They’re coming, they’re coming, our gold they have brought.

Gozbadin to Sassoon a lesson has taught.

They’ve brought forty maidens our red cows to tend.

This spring they’ll churn butter, our clothing they’ll mend.

But as they approached, it soon became clear,

the clapping went silent, something’s wrong here.

The women rushed forward and sassily taunted,

“Gozbadin, you braggard, you’re not quite as vaunted,

as boasted and toasted before your excursion.

You ran cross the mountain tops for your diversion?

So tell us, what’s up, that your head’s split in two?

And where are the maidens and where is your crew?

The forty tall maids and sacks full of gold?

And the rout of Armenia that you foretold?

You went off to Sassoon like a wolf in the wild,

and came back a poor dog, frightened and mild.”

Gozbadin exploded with loud rage and fury,

“Shut up, all you ingrates, I’ll be the jury.

You’ve never seen men like the men of Sassoon.

Each fiercer and stronger than our whole platoon.

Like mountains they tower; they use logs for arrows,

their country’s rock solid, a fort on the narrows.

Even the grass blades are sharper than swords.

They slaughtered three hundred of our fiercest lords.”

After he’d spoken, he went to the king,

running impatiently his news to bring.

The king chuckled feverishly from his high throne,

“Well done, Brave Gozbadin, you’re back with your own.

I should reward you for what you have done,

With Egypt’s great medal that’s bright as the sun,

So where is the booty and where are the maids?”

The King asked Gozbadin, “How were the raids?”

Embarrassed he shrank, his eyes to the ground,

“Long live the King, by my pledge I am bound,

I barely escaped with my life, O great lord,

Armenia has spawned a man like a horde.

He’s crazy, fears nothing, not orders nor might.

He smashed in my head with one blow in our fight.

He said, ‘I won’t give you the gold of my dad,

and the maids of Armenia they just can’t be had.

There’s no place for you in the land of Sassoon.

Let Melik himself come for tribute and boon.

Let him come, and we’ll fight it out, just me and him,

Let him come and I’ll tear him apart limb from limb.'”

The Melik of Musr flew into a rage,

“Call my whole army, a war we will wage.

ten thousand kids, new born and male,

ten thousand boys, beardless and pale.

ten thousand lads, growing with time,

ten thousand grooms, enjoying their prime,

ten thousand men with black beards and hair,

ten thousand men with heads grey and bare,

ten thousand buglers our coming to sound,

ten thousand drummers our cadence to pound.

Call them and arm them with sword, bow, and shield.

We’ll tame master David and get him to yield.

I’ll pillage and plunder Sassoon till it’s rubble.

I’ll teach Sassoon’s people to cause Egypt trouble.”

XVIII

The Melik assembled his numberless forces,

and went to Sassoon with arms, men and horses,

and when he arrived, he set up his tent,

some distance from Sassoon, where the horde went

to the river named Batma to quench their great thirst.

So many were they that when they immersed

their mouths in the water, the river went dry,

and the river flow to Sassoon slowed by and by,

until the town’s water flow came to a halt.

Distressed, Ohan wondered what was at fault.

Donning his cloak, he searched for the cause.

On a high look out, he took a quick pause,

he saw tents by the thousands, like a blanket of snow,

just as if winter had fallen below.

His warm blood ran cold and his tongue became tied.

Running back home, “God help us,” he cried.

“Woe, run away, it has come, it is here!”

“What, my dear Uncle, has caused you such fear?”

“The pain and the fire, you’ve brought on our heads.

The Melik has come here to tear us to shreds.

His army outnumbers the stars in the sky.

Woe to our lives, woe to our lands!

Gather the maids and gold in our hands.

Let us bow down, perhaps he’ll forbear.

Perhaps he’ll take pity, his sword he might spare.”

“Hold it there, Uncle, don’t blink an eye.

You’re tired and anxious, now go home and lie

down in your bed, while I take a look

at what Melik’s up to.” So David took

his leave and ran off to the old woman’s shack.

“Hey granny,” he shouted, “Look, I’ve come back.

Quick get your skewers and old iron scraps

to tie on the donkey with these tattered straps.

I’m taking on Melik the way you once said.

“O, David,” she cried, “God strike me dead.

How could your father have had such a lad?

When he went to war, a great horse he had,

a fiery steed and a waistband of gold.

And in his right hand a cross he would hold.

He had a mail shirt, defense to afford.

and a thick metal helmet and bright Lightning Sword.

And you’re off to battle with donkey and skewer.”

“Okay, okay, granny, your words could be fewer,

if you would just tell me the place where it’s hid.”

“Go, ask your uncle, you’re not just a kid.

Tell him to get it, and bring it to you.

And if he refuses, you’ll just have to do

whatever it takes to gather his trust,

but get what is yours, as is mete and is just.”

XIX

David went home to his Uncle directly,

“Hey Uncle,” he shouted loud and suspectly,

“My father had armor of which I was told,

and a fiery steed and a waistband of gold

and in his right hand a cross he would bear,

so as he made battle, he gave life no care.

He had a mail shirt, defense to afford,

and a thick metal helmet and bright Lightning Sword.

Wherever they are, Uncle, give them to me.”

“O David, my David, say how can this be?”

Ohan cried in dread, “But since your dad died,

no one has taken the horse for a ride,

nor has the sword been out of its case,

nor the mail shirt, nor the gold mace.

Just leave me alone, don’t torment me.

Take them, and use them, they’re your legacy.”

XX

David put on the armor and buckled the band.

He donned the mail shirt, his sword in his hand.

And raising the victory cross to the sky,

he mounted the Lion’s steed and riding high,

with a snap of his whip, he galloped away,

and Ohan of Great Voice, wept for this day,

“Ten thousand woes, for the steed he has taken.

Ten thousand woes, for the gold he’s forsaken.

Ten thousand woes, for the mail shirt he’s wearing.

Ten thousand woes, for the sword he’s bearing.”

On hearing this, David boiled up with rage.

He turned the steed back and charged to engage

his Uncle’s attention, making him smart.

Poor Ohan in fear changed his tune and his heart:

“Alas, my David, poor David, is lost.

Alas, he is lost at such a high cost,”

When David heard this, he sighed and calmed down.

He jumped from the horse and touched Ohan’s gown.

He then kissed his hand, and Ohan of Great Voice

with fatherly care and a nod did rejoice

at the sight of this youth, and bid him farewell,

and sent him away Musr Melik to quell.

XXI

David’s mom had a brother whose name was Toros.

This uncle’s fierce exploits unfolded before us.

When Toros got wind of the up-coming battle,

he pulled up a tree and slaughtered some cattle,

and then in the distance he was heard yelling:

“You on the plain with your tents I am telling,

David of Sassoon’s coming your way.

How many are you? You don’t want to stay.

What are you waiting for? Haven’t you heard?

He flies on his steed like a great preying bird.

Get away, while you’ve time, before he arrives.

I’m warning you, go, if you value your lives.”

Then from his shoulder he took the tree trunk,

and swinging it, cleared them away with one dunk.

From the peak David watched and then fiercely roared

like a dragon to wake up Melik and his horde:

“If you’re asleep, you’d better wake up,

and if you’re awake, you’d better stand up,

and if you are standing, you’d better gear up,

and if you are geared up, you’d better mount up,

and if you are mounted, you’d better ride on,

and don’t complain later that we were spied on,

while David attacked like a thief in the night.

So wake up, get ready, you’re in for a fight.”

Making his challenge, he spurred on his steed.

And with shocking bolts down from a cloud,

the Lightning Sword glistening followed his lead,

and struck in the midst of the Melik’s fierce crowd.

David wreaked mayhem the first half the day,

and the rush of their blood like a rising red tide,

Melik’s men by the thousands carried away,

both dead and alive in human landslide.

In the midst of the carnage was an old man,

who’d seen much of life and was known as a sage.

“Boys,” said he, “Step aside, quick, so I can

go and see David and quiet his rage.”

The old man set off to plead for his band.

He went before David, “O brave one,” he said,

“May your fist remain strong, with a sword in your hand.

May your sword remain sharp, like the thoughts in your head.

Pray hear me out though I’m old and I’m weak,

and weigh my words well as our lives you determine

What have we done that you willfully wreak

death and destruction and kill us like vermin?

Each one among us is some mother’s son.

Each one among us is some household’s light,

who’s left his dear wife and his housework undone,

her wet eyes are fixed on the road in deep fright.

His children lie shivering in their cold beds.

His parents are poor, bent over and old.

With crying and mourning, veils over their heads,

the young brides are waiting their grooms to behold.

Melik gathered these men upon pain of death.

He ordered them here crushing their will.

They’re miserable conscripts who’ve breathed their last breath.

What harm can they do you? They bear you no ill.

So pity us peons, mean Melik’s your foe.

If you’ve got a bone to pick, then in God’s name,

you two should cross swords and fight toe to toe,

and spare us unfortunate pawns in your game.”

“Well spoken, old man, you are wise as your age,”

David said to the grey beard at Sassoon’s high gate,

“But where’s the mean Melik that I might engage

in one-on-one combat and seal his dark fate.”

“You see the great tent? That’s where he sleeps.

the one with the smoke coming out of the top,

It’s not real smoke, but a foul fume that seeps,

out of his mouth as he sleeps without stop.”

Not a moment to spare, David mounted his steed.

He rode to the tent where the mean Melik lay.

At the door of the tent he arrived with great speed,

and roared at the guards who cringed in dismay.

“Where is he hiding who threatens my lands?

Call him out, in the open, we’ll fight on this field.

If he isn’t dead now, he’ll die at my hands.

His match he has met, his fate is now sealed.”

“The Melik,” they said, “Is in a deep slumber.

For seven full days his post he’s forsaken.

So far just three days have passed of that number.

Four more still remain before he’ll awaken.”

“You mean to tell me he naps while his men

are swimming in blood as deep as the sea?

For seven full days he snores in his den,

while he sends his poor troops to do battle with me.

Sleep-shmeep hear me well, this is insane.

Get him up, send him out, we shall meet in the square.

I’ll give him sleep in which he’ll remain

forever at rest with a tomb for a lair.”

The guards were now shaken and picked up a spear.

They heated it red in the campfire’s heat.

Their king snored so loud that he couldn’t hear,

as they put the hot spear to the soles of his feet.

“How can a man get a decent night’s rest

as long as these damned fleas are swarming around.”

The giant king muttered, then undistressed,

he turned himself over and slept on the ground.

So they got a huge plow from a field near the tent,

and they heated its blade on the blazing red fire,

and when it glowed bright and iridescent,

they put it against the back of their sire.

“How can a man get a decent night’s rest,

as long as these blasted mosquitoes do flit?”

Groggy, he rubbed his eyes, glimpsing a guest.

It was David who’d come to pay a visit.

He raised his head up and muttered a curse,

then he blew upon David to sweep him away,

He huffed and he puffed, but he could not coerce,

David to leave, so he shrank in dismay.

Amazement and fear engulfed his cold heart,

seeing how David withstood his fierce blows.

His bloody red eyes were fixed like a dart,

as he frowned upon David and cast a mean pose.

Seeing that David did not flinch at all,

his beastly strength drained like a wilting bean stalk.

So he sat up and thought of a way he could stall,

and he put on a smile and started to talk.

“Greetings, dear David, come in, take a chair,

you must be quite tired, let’s have a good chat.

If you’re still intent upon settling this affair,

we’ll fight one on one, okay, how is that?”

Under his tent the wily old troll

had dug a great pit some forty feet deep.

He’d had a net flung across the wide hole

with a rug for a cover, his secret to keep.

Whomever he couldn’t defeat in combat

he lured to his tent to catch in his snare.

Asking them in as his guests just like that,

they would fall in the pit as they sat unaware.

So David dismounted from his tall horse

and went and sat down upon the guest’s rug.

It gave way and he fell as a matter of course

into the pit that Melik had dug.

Melik cackled and smirked at the fate of his guest.

He ordered a millstone to close off the pit.

“You can rot in the dark, my noisome young pest,

for the rest of your life in my snare you shall sit.”

XXII

Ohan of Great Voice slept poorly that night.

Dark dreams filled his head like an unruly crowd.

O’er Egypt the sun rose with radiant light,

but a black cloud hung over Sassoon like a shroud.

Stricken with terror he jumped from his bed.

“Oh, Wife, light a candle, take hold of my hand.

It’s David, I know it, dark fate on our head.

A black cloud’s descending upon our dear land.”

“I’ll kill him, I tell you,” scowled his wife.

“Who knows where he is, the reckless ingrate?

While you’re here at home afraid for your life,

tormented by dreams about others’ fate.”

Ohan fell asleep, but was wakened again.

“O, Wife, hear me out, David’s in a tight spot.

The star over Egypt shines brighter than ten,

while Sassoon’s star fades away like a dot.”

“Dammit, old man, it’s after midnight,”

His wife scolded loudly, sharply and tart.

Ohan crossed himself, not wanting a fight,

and fell back to sleep, though troubled at heart.

He then dreamt a dream that was yet darker still.

He saw in the heavenly skyscape on high

that Egypt’s bright star was yet more visible,

while Sassoon’s was falling down out of the sky.

This time he awoke in tortured chagrin,

“A curse on your house, why’d I listen to you?

David’s in danger, he’s my last of kin.

Now get me my armor I’ve got work to do.”

XXIII

Ohan rose from bed and went to the stable.

He gave the white horse a kind slap on the back.

“Tell me old whitey, how fast are you able,

to get me to David to join the attack?”

“You’ll get there by morning if you ride on me.”

said the horse to Ohan, belly slumped to the ground.

“And what good is that? Shall I go there to be

in time for the mass at his burial mound?”

He then gave the red horse a slap on the saddle.

He too dropped its belly down to the ground.

“Dear red horse, how soon can we join in the battle

and fight on the field where David is found?”

The red horse responded, “In less than an hour,

you’ll be there with David engaged in the battle,”

“A curse on your fodder and may it grow sour,

for nought have I fed you, I’ve no time to prattle.”

Next Ohan turned to inspect the black steed.

He too dropped his belly down to the ground,

so, my black beauty, in my time of need,

can you take me there, where David is bound?

“If you wrap your legs tight and get a good grip,”

said the black horse, jumping out of his stall,

“Before your foot’s through the second stirrup,

you’ll be there with David, hold on or you’ll fall.”

XXIV

He led the black horse out for the trip,

mounting him quickly from the left side.

Before his right foot was through the stirrup,

atop Sassoon’s peaks they’d gone for a ride.

And there Ohan saw David’s horse was forsaken,

neighing and wandering through the high leas.

Below Melik’s camp was teeming with men,

endlessly streaming like waves on the seas.

He girded his waist with seven ox skins

to hold in the pressure that filled in his cheek.

He puffed like a cloud when the thunder begins

and roared from atop Sassoon’s highest peak.

“Hey, David, Ho, David, wherever you are,

remember the cross of the great sacrifice,

|and call out the name of Our Lady afar,

you’ll see light of day if you heed this advice.”

His voice rumbled loudly from heaven to earth

and reached David’s ear in the pit dark and bleak.

“Hey, hey,” David said, with great joy and mirth,

“That’s my uncle’s loud voice calling from Sassoon’s peak.”

“In the name of Our Lady on Maruta’s height,

and the immortal cross of the great sacrifice,

I call on you now to ease David’s plight.”

So bellowed he forth, in a voice that could slice.

And slice it did, for when it hit,

the millstone was shattered in thousands of parts,

uncovering the mouth of the deep and dark pit,

sending fragments to orbit like stone-hewn darts.

David rose from the pit and stood bold and wild.

Melik shuddered in fear and started to squawk,

“David, my brother, let’s be reconciled,

Let’s sup together and have a good talk.”

“No more shall I sit at the table with you,

you subhuman, cowardly, wily old man.

Now go get your arms with no more ado,

and come to the square as fast as you can.”

“Have it your way,” said the Melik with spite,

“But on one condition, the first blow is mine.”

Setting out for the square, David shouted,

“All right, take your best shot, ’cause the next one is mine.”

So they stood face to face in the midst of the square.

Melik mounted his horse with his lance in his hand.

To Diyarbekir town he rode to prepare,

for his charge against David, to make his last stand.

With clashing and tremors the great charge began.

With the force of three thousand huge stones his lance hit.

The earth shook and wobbled as Egypt’s king ran

and the impact raised clouds of thick dust and grey grit.

“An earthquake has struck,” said the people aghast,

frightened in far off lands jarred by the blows.

“No,” said some others, “It’s just some great blast,

caused by the clash between two mortal foes.”

“I’ve struck David dead, with only one blow,”

Melik bragged to his men, smug with conceit.

“Don’t be so sure, I’m next to go,”

said David unfazed, “I’m still on my feet.”

Melik stammered, “I started too close the first time.

Next time I’ll get you, I’ll build up some speed.”

Melik mounted his horse and started to climb

over the hills to a far land indeed.

This time from Aleppo he spurred on his horse,

and stirred up a storm, lightning, thunder and rain,

and shaking the world with yet greater force,

he started his charge with grunting and strain.

He came and he struck, and the sound of the blow

left the people close by as deaf as a stone.

“The House of Sassoon is finally laid low,”

the Melik declared with a snide, haughty tone.

“Not so fast,” called out David, “I’m still on my feet.

Now you’ve had your turn, this time I will go.”

“Just one more time and you’ll meet your defeat,

I started too close and was charging too slow.”

The third time Melik went back to his home,

and starting from Egypt he charged with his lance.

Spurring his horse across the sea foam,

he took aim at David across the expanse.

He struck him once more with all of his strength,

a huge, heavy blow packing hundreds of tons.

The impact unsettled Sassoon’s breadth and length,

raising a dust cloud that darkened the sun.

Three days and three nights dust darkened the skies,

hanging about like an ominous sign.

Three days and three nights, there were wailing and sighs,

mourning the death of their nation’s scion.

Then on the third day, in the midst of the dust,

David emerged, like a peak through a cloud.

Majestic and tall, standing like a stone bust,

he shouted to Melik, who was shaken and cowed.

“Melik,” he said, “Guess whose turn it is next,

Hope you are ready to meet your demise,”

Melik’s heart trembled as though he were hexed,

and the haughty king’s ego was cut down to size.

Melik fled to a pit in the earth’s darker zones,

which he’d dug for himself in terror and fear.

He sealed it securely with forty millstones,

and forty thick skins of oxen and deer.

A lion was David, like his father Mher,

growling, he rose to set things aright.

He mounted his horse, storming into the air,

with the great Lightning Sword in his hand glistening bright.

Melik’s wicked old mother came to entreat

David for mercy, distraught, with wild hair,

“My hair, sire David, trample under your feet,

I’ll bear your first blow, if my son you will spare.”

David was poised to strike the next blow.

Melik’s sister came forth to settle the strife.

“Your sword’s second cut, I’ll undergo,

straight through my heart, just spare him his life.”

The time had arrived to strike the third blow,

“Let no one dare come and stand in my way.

With God’s help we’ll at last be rid of this foe,

but I must strike now with no further delay.”

And strike he did, with fury and sound,

on his fiery steed he soared through the sky,

A lightning bolt flew from his sword to the ground,

with such force it was certain that Melik would die.

The lightning bolt struck on the seals to the pit,

piercing the skins and the stones through and through.

It struck Melik’s heart and soon as it hit,

it severed the fiendish king’s body in two.

Melik then called from his dark hiding place,

“I’m still alive. Hit me once more.”

When David heard this, he screwed up his face,

knowing the force that the Lightning Sword bore.

“Melik,” he said, “Get up, move a bit,”

As Melik arose and cautiously crept,

a hole opened up in the place he’d been hit,

and his body collapsed in two as he stepped.

When Melik’s troops saw what had become,

of their miserable leader, they scrambled in fear.

David promised them pardon if they’d succumb

and urged them sincerely to lend him an ear.

“Heed me, men of Egypt, you’re tillers of soil.

You’re hungry and tired, you’re longing for home.

Why have you come to Sassoon to despoil

our land and our people? Why do you roam?

You’ve a thousand and one worries and pains.

You’ve a thousand and one troubles to bear.

We too have our homes, our families and strains.

We too have our young and our old who need care.

Can you explain why you’ve traipsed over here?

Are you restless and bored with your calm peaceful lives?

Your land and your kinfolk, aren’t they dear?

Have you tired of tilling your fields so they thrive?

By the route that you came here, you now must go back

to your homeland of Musr in Egypt afar.

But be warned if you ever raise arms and attack

us again by some ruinous, ill-fated star,

No pit that you dig can be dug deep enough.

no millstones you stack can be piled high enough,

to spare you the wrath of this son of Sassoon

or the bright Lightning Sword with its piercing typhoon.

Then only God will know,

who will regret it more,

we, who must go to war,

or you, who made us your foe.

* * *

translated by Thomas J. Samuelian, USA © September 1997